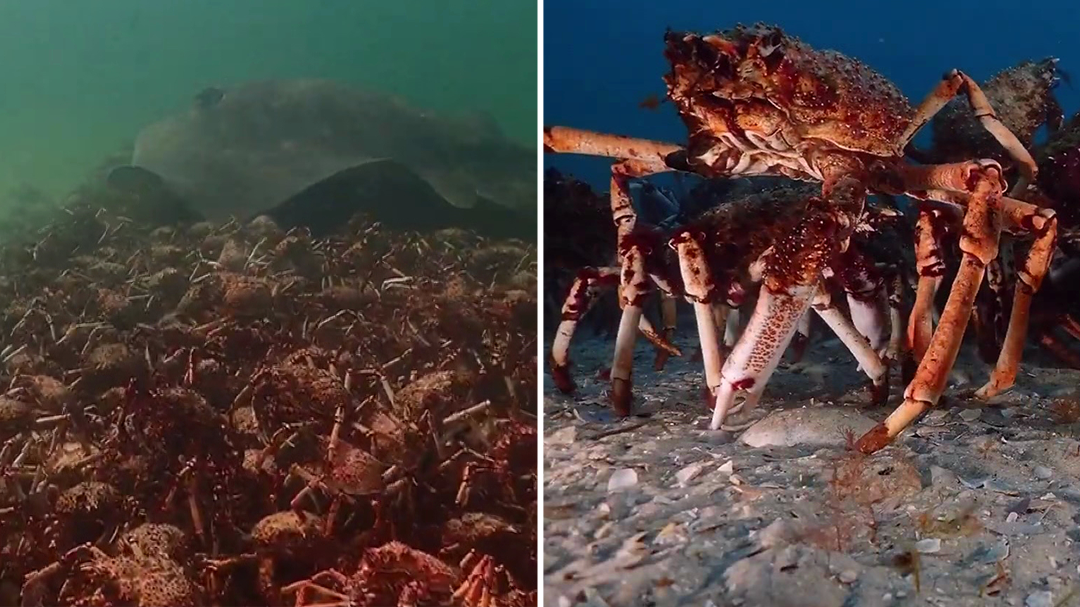

Thousands of native spider crabs gather underneath Melbourne’s coast every winter. Researches want to know why

Every winter armies of native spider crabs gather in the shallow waters of Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay, in what is one of the world’s most enduring ocean mysteries.

Within months, the crustaceans are gone, and disappear into the depths of the sea and no-one really knows where they go.

Researchers are still working out exactly why the phenomenon occurs, but hold several theories as to what may be going on.

Mystery surrounds aggregation

There is little scientific data collected around spider crabs, Deakin research fellow in spider crab ecology Dr Elodie Camprasse told 9news.com.au.

But she believes the species head to the shallow waters to crawl out of their shell, a process that leaves them extremely vulnerable.

“They need to grow out of their shell and harden a new shell,” Camprasse said.

“We think that process takes a day or two. During that time, the spider crabs are soft, which means they are vulnerable to predators. That’s the reason why we think they come together in such big numbers.

“If they are in the middle of a spider crab pile, it could reduce their chance of becoming a meal for predators (including) stingrays or smaller sharks. They try and munch on them often as they are easy targets.

“Their shell acts as an armour.”

Researchers observed more than 50,000 crabs gather over a three day period last year in the bay.

The crabs, usually orange to red-brown can reach 16cm across their shell and 40cm across their legs.

They usually generate the most attention during the winter months, when they come together also known as “aggregation”.

Spider crabs have also been observed at different locations in Victoria, including on the Mornington and Bellarine peninsula.

“We don’t know much at all about how they choose the locations or what might trigger the aggregations,” Camprasse said.

“Some people think it might be related to water temperature or the moon cycle. We just don’t have enough data to say why.”

Community led research

A team of scientists at Deakin University hope the public can help learn more about the species through community led research.

Although the main project is based on the Mornington Peninsula, the citizen science program seeks the assistance of everyone, from recreational fishermen, divers, charter tour operators to collate data on the aggregation.

“These aggregations seem to happen at random times,” Camprasse said.

“Unlike some citizen science programs, we need our members to record both when they see spider crabs, but also when they don’t, so we can try and establish a pattern of when the aggregations happen.”

She said until more research is funded into the species, they will continue to remain a mystery.

“What fascinates me is how little we know about this species, they usually come together in deeper water and away from the shore, but this phenomenon has been potentially happening for more than decades,” Camprasse said.

“For them to come together in shallow water, like you can see them and yet there are so many answers we don’t have about their basic biology, it is very interesting.”