How a Melbourne socialite lost her nationality in an instant

When a wealthy Australian socialite secretly married in a foreign embassy in London, she instantly lost her nationality. Yet, after decades, and a world war, it was finally restored.

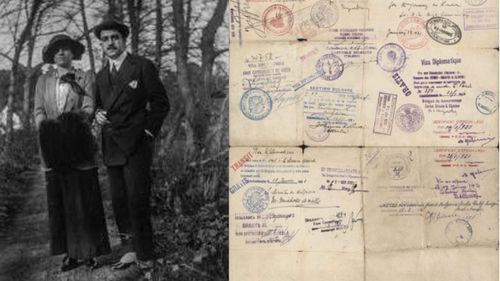

It was within the walls of the Ottoman Embassy in the Marylebone district of central London in September 1913 when Florence Winter-Irving wed Turkish aristocrat and diplomat, Chefik Bey Muftyzade.

The marriage would elevate the then 28-year-old, and youngest daughter of the Victorian grazier, magistrate and politician, William Winter-Irving, to the title of ‘Madame Chefik Bey’.

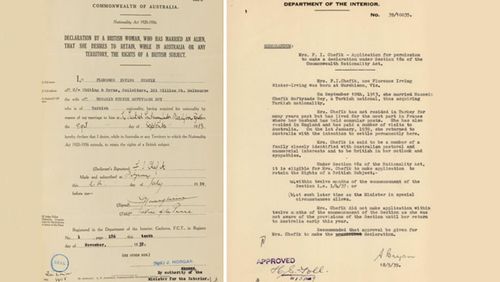

However, citizenship laws of the time dictated a married woman’s nationality was tied to that of her husband. As Chefik was deemed an “alien”, meaning a non-British subject, it followed Florence was too. It would have far reaching consequences for the pair.

A golden childhood

Florence was the youngest daughter of the Winter-Irving’s 11 children, and the ninth born. She grew up surrounded by privilege, built from wealth made during the Gold Rush, in Central Victoria.

“Florence lived at the substantial property, Noorilim, which at the time was one of Australia’s most stately regional homes,” Florence’s great-granddaughter, Janan Greer, tells nine.com.au.

The estate, north of Melbourne in Murchison in Central Victoria, was designed for Florence’s father by architect, James Gall. It was built in 1879 and is surrounded by 20 acres of land. Today it is owned by Australian entrepreneur Rod Menzies.

Mr Winter-Irving died at Noorilim in 1901, leaving behind his widow Frances Amelia.

“Florence ended up living this very Cosmopolitan lifestyle that was a far cry from the ladies’ tea parties in the family’s second residence in Melbourne.”

Ms Greer says a fear of being left her mother’s nurse maid compelled Florence to venture far from home.

“She had this huge phobia about being, I guess, a spinster and being left behind to look after her widowed mother. So, she took off overseas,” she says.

Ms Greer says it was likely Florence was visiting siblings in Germany and England at the time she met Chefik, then third secretary at the Ottoman embassy, in London.

“I was always told they met at a dinner party at the Turkish Embassy,” she says.

“So, it’s a little Downton Abbey… their meeting has got a bit of a Mr Pamuk-vibe. When I saw that episode, I thought ‘oh my god that’s been based on my family'”, she laughs.

“Florence ended up living this very Cosmopolitan lifestyle that was a far cry from the ladies’ tea parties in the family’s second residence in Melbourne.”

Misunderstanding of cultures

Yet, Ms Greer says the Florence and Chefik’s union was frowned upon by the bride’s family.

“It was very controversial. Apparently, her family was not pleased at all. The fact that my great grandfather was Turkish and a Muslim must have been pretty confronting for them,” she says.

On October 2, 1913 a local Australian newspaper published news of the marriage with the headline “Into the Harem” – falsely suggesting Florence was now one of Chefik’s many wives.

Yet in reality, Ms Greer says Chefik’s father was a Pasha – a man of high rank in the Ottoman Empire- and mingled with prominent diplomatic leaders, kings and queens.

‘She obviously had no idea war was on the horizon and that things would go the way they did’

“Chefik’s family was so much more worldly and of a much higher social standing than Florence’s, so it’s ironic they were so upset by the match,” she says.

As well as the ignorance surrounding their relationship, Florence and Chefik would soon face one of their most difficult periods together – living as “enemy aliens” during a world war.

“When she married my great-grandfather, she obviously had no idea war was on the horizon and that things would go the way they did,” Ms Greer says.

“Had she known all of that, I often wonder whether or not she would have chosen the same pathway because her life became very handicapped as a result of that.”

Living as ‘enemy aliens’

A year into their marriage, in late 1914, Britain and Turkey went to war.

“She had brothers who were fighting for Australia in the war and on the flipside, her husband’s father was the Minister for Foreign Affairs, at one point, for Turkey at during the first World War,” Ms Greer says.

“So, the family is totally split in terms of loyalties and divisions. What I can gather is that despite this, the siblings remained in touch and wrote to each other. Sadly, she never saw her mother again after the marriage.

“And the family today is still very much connected, so it couldn’t have severed all ties.”

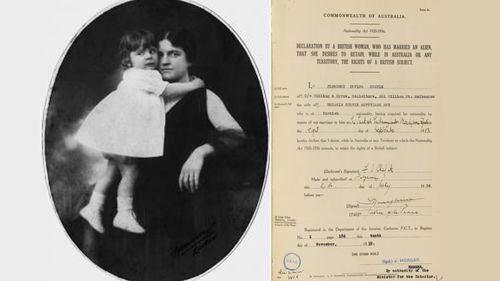

Florence and Chefik fled London at the onset of war, first to Constantinople and then to Berlin where Chefik was posted. In 1916, Florence gave birth inside the Turkish embassy in Berlin to the couple’s only child, a son named Reshid.

Money was tight for the family. With her ‘enemy alien’ status, Florence was no longer able to access funds from her family back in Australia.

According to documents held in the collection of the National Archives of Australia, it wasn’t until after the WWI Armistice, or ceasefire, in 1918 when the family were living in Switzerland that 8000 pounds of Florence’s Australian money was released.

‘The siblings remained in touch and wrote to each other. Sadly, she never saw her mother again after the marriage.’

Florence’s lawyers would eventually petition the then Australian Prime Minister Stanley Bruce to intervene so the family could access more funds withheld over the lack of a peace treaty with Turkey.

Adding to the family’s financial strains, in or around 1922, Chefik’s father quit his position with the Turkish government when Mustafa

Kemal Atatürk came to power and the Ottoman Empire folded. Chefik also left the new regime soon after his father.

Ms Greer says family legend has it that Atatürk’s banning Turkish government officials from having foreign wives was linked to the decision. Outside of Chefik’s marriage to Florence, his father was married to his second wife, an Italian.

“The family’s once opulent lifestyle took a battering after the war and my grandfather used to tell stories about being a boy in Switzerland with his parents raiding his piggybank for cigarette money,” Ms Greer says.

“They clearly found it really hard to adapt to a new way of living that didn’t involve having others take care of their needs and expenses.”

The long trip home

Florence would eventually return to Australia with son Reshid in early 1939. By this stage she was gravely ill and would not live out the year.

“She came back to Australia, we believe, to spend the last years of her life at home. She was terminally ill when she got back,” Ms Greer says.

It was a bittersweet return. By this stage, citizenship laws had changed to allow her to regain her Australian citizenship.

Chefik followed his wife and son a few months later. He remained in Australia where he was naturalised, as an Australian citizen in 1949.

“He forfeited all of his nationalities, Albanian, Turkish and died an Australian citizen,” Ms Greer says.

Reshid would also continue to live in Australia, building a life here and becoming a notable artist, with several of his works in the National Portrait Galleries collection.

Archivist Patrick Ferry, and Janan Greer will be sharing more about Florence Winter-Irving’s life in a Royal Historical Society of Victoria talk on 9 December. Registration is free.