The fall of tech star Elizabeth Holmes – from Silicon Valley to the courtroom

Six years ago Elizabeth Holmes was set to become Silicon Valley’s next tech superstar.

Now Ms Holmes is facing criminal allegations in a courtroom in San Jose, California.

Ms Holmes was accused of masterminding a fraud that duped wealthy investors, former US government officials and patients whose lives were endangered by a blood-testing technology that didn’t fulfill what it was promised to do.

If convicted by a jury in a trial that begins today, Ms Holmes could be sentenced to 20 years in prison, which would be a significant reversal of fortune for the entrepreneur whose wealth was once pegged at $6 billion.

That amount represented her 50 per cent stake in Theranos, a Palo Alto, California, biotech startup she founded in 2003 after dropping out of Stanford University at the age of 19.

The three-month trial may also shed light on how style sometimes overshadowed substance in Silicon Valley, which prided itself on an ethos of logic, data and science over emotion.

Ms Holmes’ saga peeled back the curtain on a “fake it until you make it” strategy that was adopted by other ambitious startups who believed that with just a little more time to perfect their promised breakthroughs they could join the hallowed ranks of Apple, Google, Facebook and other tech pioneers.

“I came away thinking she was just a zealot who really believed her technology would really work so maybe she could fudge just a little bit,” author Ken Auletta said.

Auletta wrote extensively about Silicon Valley and was given behind-the-scenes access to Ms Holmes for a 2014 profile in The New Yorker magazine.

“I came away thinking she really believed what she was doing was a public good. And if it had worked, it would have been a public good.”

Ms Holmes was an adept marketer while pitching the premise that Theranos would help people avoid having to tell their loved ones “goodbye too soon”.

Theranos — a name derived from the words “therapy” and “diagnosis”— claimed to be perfecting a technology that could test for hundreds of diseases by extracting just a few drops of blood from a quick finger prick done at “wellness centres” across the US.

Ms Holmes promised the samples would be tested in a specially designed machine named after famed inventor Thomas Edison.

The technology was said by Ms Holmes to cost a fraction of traditional tests that require a doctor’s referral and vials of drawn blood before lab processing that could take days to deliver results.

A well-connected board of directors helped burnish Theranos’ credibility.

The board included former US Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger and George Shultz, former US Defence Secretary James Mattis, former Senator Sam Nunn, former Wells Fargo Bank CEO Richard Kovacevich, and her former adviser at Stanford, Channing Robertson.

Mr Robertson quit his tenured job as a chemical engineering professor after he decided Ms Holmes had Beethoven-like qualities.

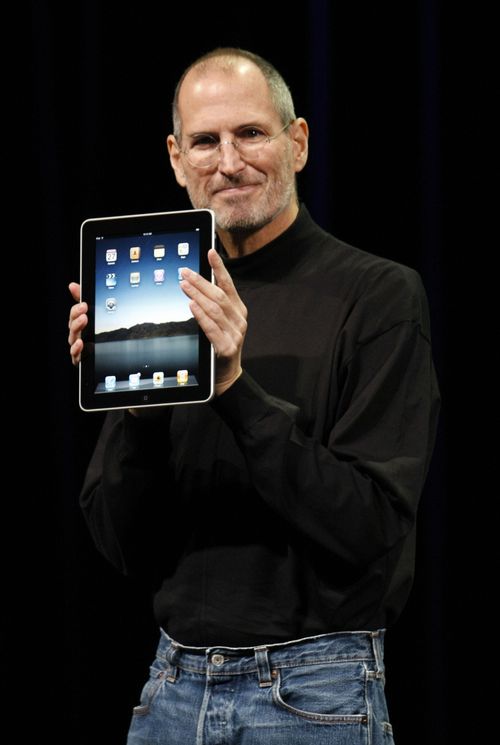

Ms Holmes tried to cast herself in the mould of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, even adopting his habit of wearing mostly black turtlenecks.

Ms Holmes also raised nearly $1.2 billion before Theranos collapsed, triggered by a series of explosive Wall Street Journal articles that revealed serious flaws in the company’s technology.

The Journal articles spurred an inquiry by the US Food and Drug Administration and a civil lawsuit filed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

The SEC case resulted in a $676,000 settlement without an admission of wrongdoing, but still proved to be the end of Theranos, which shut down in 2018.

Large amounts of the money poured into Theranos came from billionaire investors, including media giant Rupert Murdoch, Walmart’s Walton family, the DeVos family that included former U.S. Education Secretary Becky DeVos, Mexico business mogul Carlos Slim and former Oracle CEO Larry Ellison.

Some of those investors, as well some of Theranos’ former board members, are expected to testify during the trial presided over by US District Judge Edward Davila.

Ms Holmes may take the witness stand, based on court documents filed leading up to the trial. If that happens her lawyers have indicated that she would testify that some of her statements and actions while running Theranos were the result of “intimate partner abuse”.

She is expected to accuse the company’s chief operating officer and her secret lover, Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, who faces multiple fraud charges in a separate trial scheduled to begin next year.

“That will be extraordinary,” predicted Auletta, who observed and interviewed Ms Holmes and Mr Balwani together on multiple occasions while he was writing his profile.

“My impression was she was the dominant one in that relationship. If she started a sentence, he would wait for her to finish it.”

Mr Balwani’s lawyer has denied Ms Holmes’ allegations.

It was unclear whether the licence plate on the car that Mr Balwani used to drive to Theranos’ former headquarters was becoming part of the evidence submitted during the trial.

It read: “VDVICI,” an abbreviation for the triumphant words Julius Caesar is supposed to have once written to the Roman Senate, “veni, vidi, vici” — Latin for “I came, I saw, I conquered.”